It’s morning. You wake up, eat breakfast and go about your daily routine. After lunch, the midday slump hits you hard and you take a nap. You awaken groggily — did you miss anything important while you were asleep? Nope, your world has remained pretty much the same. It’s been two months of the same routine, food, sights and smells, you’re bored and frankly, you don’t know if you can remember how to work a puzzle feeder.

Did you think I was referring to the life of a person stuck at home during a city lockdown? Not quite – I was talking about the wildlife, or more specifically the wildlife currently residing in rescue centres. This isolation and boredom that millions around the world are currently facing, while hard to bear even for humans, is understood to only be a temporary condition. But for animals in wildlife rescue centres, this prolonged lack of cognitive stimulation directly affects their chances of a new life in the wild after the pandemic.

How COVID-19 can impact wildlife’s cognitive abilities

A wildlife rescue centre is not a zoo. Many of the animals in rescue centres were victims of wildlife trafficking and undergo rehabilitation to prepare them for a life back in the wild. The process of rehabilitation and release is a complicated affair, filled with bureaucratic red tape, and can take months and years. Part of this journey involves the continuous monitoring of victim animals by vets, animal behavior biologists and keepers to ensure that they are exhibiting normal, “wild” behaviour. Signs of domestication — such as losing the ability to forage or hunt, preferring to wait on or approach humans for food — can become the difference between life and death for these animals in the wild, many of whom are endangered and in high demand by the exotic pet trade.

Binbin and Bonbon, a pair of Bornean sun bear siblings, have resided in Tasikoki Wildlife Rescue and Education Centre for over 10 years since their rescue as cubs in a raid by authorities that followed an intense car chase which also yielded several baby gibbons and an orang-utan cub. The likelihood of their return to the forests of Kalimantan remains low, in large part due to the fact that they will face huge difficulty in adapting to life in the wild. “Sun bears that have been kept in captivity tend to have their fear of people broken down, they are habituated to see humans as a source of food. This is virtually impossible to undo.” explains Mr. Simon Purser, former Tasikoki Wildlife Rescue and Education Centre manager. Indeed, when wildlife loses their ability to forage or hunt for food in the wild, it puts their lives at great risk. Sun bears in particular have an extremely keen sense of smell and can sniff out a village from kilometres away. “They end up raiding someone’s kitchen, and this creates human-wildlife conflict situations.” Mr Purser said.

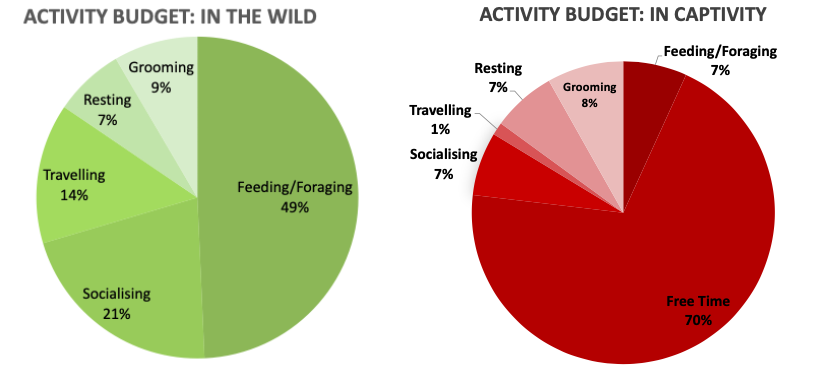

Thus, cognitive stimulation is essential for these animals waiting to be released back to their natural habitats. In the wild, foraging animals typically spend up to 6 hours a day searching for, processing and eating their food. In captivity, food is prepared and delivered to them in their cages, which can deprive wildlife of the opportunity to fully express their normal behaviour of foraging and hunting. At wildlife rescue centres, “enrichments” — food, scents or toys designed to stimulate an animal’s cognitive abilities — routinely prepared by wildlife keepers or volunteers are used to keep animals occupied for longer periods of time and to allow them to hone the foraging and hunting skills that are critical to their survival in the wild. Due to the social distancing measures and travel restrictions currently in place during this COVID-19 pandemic, rescue centres like Tasikoki are finding it difficult to keep up with the manpower demand to ensure that these animals get their enrichments. This can have dramatic consequences on the likelihood of these animals returning to the wild in the future.

“(Under normal circumstances) volunteers are involved in the enrichment programme to stimulate the livelihood of the animals at our centre and this also cannot be executed to the fullest anymore due to the limited staff that we have and without funds we cannot hire additional staff to take on these duties.” said Dr. Willie Smits, renowned conservationist and the founder of Tasikoki Wildlife Rescue and Education Centre. For independent wildlife rescue centres like Tasikoki, enrichment-making is a role typically filled by wildlife volunteers, some of whom fly from across the globe for this unique opportunity to work in close proximity with wildlife. As the only wildlife rescue centre in North Sulawesi, Tasikoki does vital work in intercepting smuggled wildlife on their way out of Indonesia into the Philippines, a major wildlife export hub.

Lack of funding hampers Tasikoki’s wildlife rescue work

Located only 30 minutes from the nearest large Indonesian port from the Philippines, Tasikoki is at a critical interception point of trafficked wildlife, yet it receives no government funding for their valuable work. “We mostly do depend upon donations (to support our operating costs).” says Dr Smits. As such, allowing volunteers to take charge of crucial wildlife rescue centre activities such as enrichment-making allows the centre to reduce their operational costs, while simultaneously garnering more donations for the centre and increasing the scope of their outreach and education programme. Dr Smits explained that “more than 50% of all the costs of running the wildlife rescue centre comes from volunteers and school visits.” Visitors from around the world are invited to stay and volunteer at Tasikoki as a thank you for their donation, and Tasikoki also organises activities and outings for visiting donor schools.

Thus, prevailing travel restrictions have far-reaching implications on the operations of the wildlife rescue centre, and not just in terms of enrichment delivery for the animals. “At this moment, there are no volunteers, no school groups visiting our facilities anymore and we can also not have short-term visitors coming for a day that might bring in donations.” said Dr Smits. “As a result of the (COVID-19) crisis, some of the donors that have supported us in the past have to withdraw their contributions because they themselves end up in financial problems.”

In addition, operating costs of the centre have gone up due to price increases in food (a vital expense for the centre, who feeds over 400 animals daily) and protective gear like masks and gloves that are not only essential equipment for vets and other clinic staff, but also critical in preventing the spread of disease among workers at the centre. “Fortunately all of our staff is still healthy. None have been infected and fallen sick so all the staff are still there taking care of the animals although we do not know how to pay their salaries. Still people come even in the very difficult time of the fasting month where people cannot eat, they still have to do the job even without secure income and with great difficulty in obtaining the food to bring to the animals. These are truly heavy times and I really appreciate the staff still putting in all these efforts to make sure that the animals we rescued with such great effort (are taken care of).” Dr Smits says.

COVID-19 highlights need to re-think NGO funding

It is evident that the current pandemic has highlighted the instability and risks of relying on private donors for funding. “It is clear that we are just like markets, we are very much exposed to risks and trends — if there is another economic crisis, automatically the income for NGOs (will be impacted).” Dr Smits said. His foresight has led him to

invest in projects that create sustainable sources of income and that reduce costs for the centre, such as engaging local farmers in producing sustainably-grown palm sugar and growing organic produce onsite which creates new sources of income for the rescue centre. But it takes years for these projects to reach a scale large enough to sustain the operations of Tasikoki, which employs over 30 staff members and houses more than 400 animals. Without governmental support, the operations of this wildlife rescue centre continue to hinge on the public’s willingness to contribute to its cause. “If there are people who are more experienced in using social media and using their networks to try to ask other people to help — even if it’s just a little bit of money: if a lot of people can be reached and contribute a bit, it might help us through this crisis until we can reopen our centre to visitors.” said Dr Smits.

Tasikoki is the last hope for many wildlife saved from the global trafficking network. “These are difficult times for everyone, but hopefully we realise that it is not humans alone on this planet, we need to live in balance with wildlife and nature.” Dr Smits urged. “We can only solve this problem if we all work together”.

If you would like to make a donation to Tasikoki Wildlife Rescue & Education Centre, you can do so at bit.ly/tasikoki-donate